|

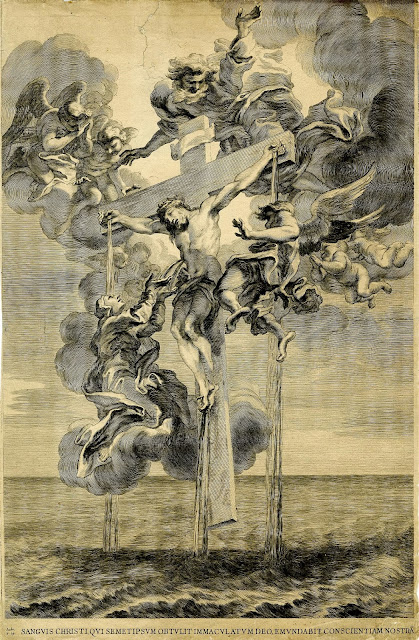

| Francois Spierre after Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Sanguis Christi Italian, c. 1670 London, British Museum |

Since childhood one of my favorite prayers has always been the Anima Christi:

“Soul of Christ, sanctify me

Body of Christ, save me

Blood of Christ, inebriate me

Water from Christ's side, wash me

Passion of Christ, strengthen me

O good Jesus, hear me

Within Thy wounds hide me

Suffer me not to be separated

from Thee

From the wicked enemy defend me

In the hour of my death call me

And bid me come unto Thee

That I may praise Thee with Thy

saints

and with Thy angels

Forever and ever”1

When I first came upon it as a child I wasn’t even sure what the word “inebriate”

meant. Later I learned that it means

basically to make intoxicated, to make drunk or, as the Merriam-Webster

definition has it “to exhilarate or stupefy as if by liquor”. I like the “to exhilarate” definition

best.

I mention this because one of the most affective images I have ever

seen is an engraving after a drawing by Gian Lorenzo Bernini that was published

in a 1972 article by Irving Lavin, one of my graduate school professors.2 It

shows a dramatic picture of Christ on the cross, raised high in the air,

surrounded by angels, with God the Father in the sky above and the Virgin Mary,

also raised into the air, kneeling to one side.

From the wounds of Christ blood pours in abundance, dropping from His

hands and feet into an ocean of blood already poured out below. From the wound in His side, blood pours into

the hands of His mother. This is the

image that I have carried in my mind for decades whenever I think of the Blood

of Christ which can inebriate. It is the

ocean of Divine Mercy that is available to us.

,%20Teylers%20Museum_2.jpg) |

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Sangue di Cristo Italian, c. 1669 Haarlem (NL), Teylers Museum |

Lavin’s 1972 article brought this image to the attention of the art

historical community. He pointed out that

this image was one of the very last works ever made by Bernini, being made when

the artist was 80 years old, two years before his death in 1680. In fact,

only the drawing was made by Bernini, although he commissioned an engraver

named Francois Spierre to make an engraving of it and also commissioned an

unnamed artist to make a painting, which he positioned at the foot of his own

bed. The engraving was actually intended

for use by Bernini’s nephew, Father Francesco Marchese, as the centering image

in a book which he wrote in 1670 called Unica

speranza del peccatore (The Sole Hope of the Sinner) which was

intended to serve as a guide for living a holy life and dying a holy death in

confidence of salvation through the effects of Christ’s sacrifice.

|

| Guillaume Courtois, Il Borgonone after Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Blood of Christ Italian, 17th Century Private Collection One of three known versions of paintings after Bernini's drawing. |

The visual representation of the saving power of Christ’s Blood has no

echo in our current, visually impoverished age.

Such an affecting image could probably not be produced today. It would probably be dismissed as too

gruesome. But it was not always so. The saving power of Christ’s Blood has a long

visual history in several different, but related groupings, none of them

sparing in their representation of the bloodiness of the sacrifice of Calvary.

The Mystic Winepress

The most common specific image of the saving power of the Blood of

Christ is the image known as the Mystic Winepress or Christ in the

Winepress.

Simply put, the image is one

in which Christ is shown standing, but sometimes lying or sitting, inside a

winepress, as though He was a bunch of grapes, while the pressing beam of the

press bears down on His body and His blood pours into the trough as if it was the

juice of the grape. It is a powerful

image and, to modern eyes, both a bit frightening and a bit bizarre. This is because the modern age has lost the

connections that would have been apparent to those who saw it during the late

middle ages and early modern period, when it was most frequently used.

It is very much a devotional picture, as are,

indeed, all these images of the power of Christ’s Blood. They are to be contemplated and revered as

visual expressions of a truth of faith.

|

| Mystic Winepress Tapestry Flemish, c. 1500 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The Mystic Winepress was most frequently used in northern Europe. It occurs only rarely in Italy and scarcely

at all in the British Isles. So, one can

say that, with the exception of Italy, it is most frequent in countries where

the winepress was actually used in the production of wine.

The earliest example I could find dates to the end of the 14th

century, but it is already a developed image at this point, so it must have

appeared somewhat earlier in time. Rather

surprisingly, it is one of the few Catholic devotional images that was retained

by the Protestant reformers, who generally loathed and destroyed almost any

kind of religious imagery, especially imagery regarding the Eucharist. However, in both Catholic and Protestant

regions it seems to have mostly died out by 1600, although there is one late example from the

18th century.

There are two types of presses in evidence in the images.

One is a contraption in which two stationary uprights

support a beam which is moved down by a centrally placed screw mechanism, or one in which the two uprights are screws which are used to move the central beam.

| |

|

|

| Christ in The Winepress Tile Mold for Pastries German, c. 1430-1470 Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin |

|

| Man of Sorrows and the Mystic Winepress From the Hours of Catherine of Cleves Dutch (Utrecht), c. 1435-1445 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS. M 917-945, fol. 121 Here we see two related images. In the main picture, Christ directs the Blood from his wounded side toward the ground. In the lower margin the Mystic Winepress drains His Blood into the chalice used at Mass, underlining the connection between His death on Calvary and the Eucharistic celebration, the Mass. |

|

| Mystic Winepress French, 1460-1470 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

,%20End%20of%20the%2015th%20Century_Paris,%20BIbliotheque%20nationale%20de%20France,%20MS%20Francais%20166,%20fol.%20123v_1.jpg) |

| Mystic Winepress From the Bible moralisee de Philippe le Hardi French (Provence), End of the 15th Century Paris, BIbliotheque nationale de France, MS Francais 166, fol. 123v |

| |

|

|

| Mystic Winepress Window French, 1552 Conches-sur-Ouche, Church of Sainte-Foy |

|

| Anonymous after Maarten van Heemskerck, The Fall and Salvation of Mankind, Christ in the Winepress Dutch, 1568 London, British Museum |

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, Christ in the Winepress Flemish, c. 1600-1619 London, British Museum |

|

| Anonymous High Altar Frontal, Christ in the Winepress German, c. 1740 Mindelheim, Jesuit Church of the Annunciation |

The other is a somewhat simpler form in

which there is only one stationary pole on which the beam is looped. At the other end of the trough is a screw on

which the other end of the beam is forced down.

In both kinds of press, the Cross is often substituted for the pressing

beam, so that Christ is pressed by the Cross itself, a further layer of

meaning.

|

| Christ in the Winepress German or Danish, 15th Century Brøns (DN), Parish Church |

|

| Mystic Winepress From Commentaries on the Gospel of John by Nicholas of Lyra Austrian (Mondsee), c. 1400-1410 Vienna, Österreichischen Nationalbiliothek MS cod 3676, fol. 14r |

|

| Allegory of the Sacraments German, 16th Century Colmar, Bibliotheque municipal MS 306

This image shows the relationship of the Blood of Christ to the sacraments. It is the power house that supplies the graces they confer. Directly below the winepress is the sacrament of the Eucharist, as the priest gives Holy Communion to a keeling lay person. On the left from top to bottom are Confirmation, Baptism and Penance. On the right from the top are Extreme Unction (now the Anointing of the Sick), Ordination and Marriage. |

|

| Attributed to Bergognone, The Mystic Winepress Italian, c. 1500 Milan, Santa Maria Incoronata |

|

| Ego Sum Pastor Bonus From a Book of Hours Flemish (Tournai), 16th Century New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 78, fol. 3v |

|

| Mystic Winepress German, c. 1500 Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum |

|

| Mystic Winepress From the Hours of Ulrich von Montfort Swiss, ca.1515-1520 Vienna_Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek |

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, Christ in the Winepress Flemish, c. 1600-1619 London, British Museum |

|

| Marco PIno, Christ in Glory above the Mystic Winepress Italian, c. 1571 Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana Shown filling jars with the Precious Blood from the winepress are a Pope (probably either Gregory the Great or Urban IV) and Saint Jerome. Two other unidentified saints fill theirs in the background. |

|

| Mystic Winepress Window French, c. 1600 Paris, Church of Saint Étienne-du-Mont |

The Fons Vitae

A development from the Mystic Winepress is the Fons Vitae or Fountain

of Life. This image is a little less

disturbing than the winepress to modern eyes, while remaining a bit

strange. In these pictures Christ stands

in or near a fountain into which His Blood is poured. In some images it pours directly from His

wounds, while in others it pours from some other source. In several images it is shown as the means by

which the sins of humanity are washed clean and forgiven.

|

| Allegory of the Eucharist German, c. 1470-1490 Washington, National Gallery of Art The Blood of Christ flows out to liberate souls in Purgatory. |

|

| Fons Vitae From a Diurnal Dutch, c. 1470-1495 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS W 27, fol. i |

|

| Goswijn van der Weyden, Fons Pietatis Flemish, c. 1500 Götenborg (SV), Götenborg Konstmuseum

This image, by Rogier van der Weyden's nephew, is a twist on the traditional Mercy. Christ and His Mother kneel on either side of the fountain which is flowing with His Blood and plead for mercy on the souls in Purgatory to the Father who is shown in Heaven. Christ shows His wounds and the Virgin her breast as a reminder of the actions that warrant their pleas. Angels fill and empty chalices of Blood on those suffering in Purgatory. |

|

| Jean Bellegame, Fount of Life Flemish, 1500-152 Lille, Musée des Beaux-Arts In another version of the same idea Bellegame presents us with the image of the way in which the Blood of Christ restores sinners to innocence. At the left, the weary sick souls of sinners enter and remove their garments, watched over by angels. In the center they enter the Fountain of Life, where the Crucified Christ pours His Blood into the fountain for them to bathe in. At the right the rejuvenated souls enter Paradise, welcomed by the saints.

|

|

| Adriaen Collaert after Ambrosius Francken, Faith Purifying Human Hearts with the Blood of Christ Flemish, c. 1575-1612 London, British Museum Another image of purification through the Blood of Christ. |

|

| Jan Baptist Barbe, Fons Vitae with Four Jesuit Saints Dutch, c. 1593-1649 London, British Museum |

|

| Matthias Greuter, Allegory of the Fall and Redemption of Mankind German, 1586-1638 London, British Museum Here the Blood pours forth from the Lamb of God while Christ beckons the original sinners, Adam and Eve, to be saved.

|

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, Christ as the Fount of Life, Fons Vitae Flemish, c. 1600 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

The Sea of Blood

|

| Giotto, Crucifixion Italian, c. 1300-1304 Padua, Scrovegni/Arena Chapel |

|

| Attributed to Nicolo da Bologna, Crucifixion Single leaf from a Missal Italian, c. 1390 Cleveland, Museum of Art |

|

| Crucifixion German (Rhenish), c. 1450-1500 Frankfurt-am-Main, Staedelsches Kunstinstitut und Staedtische Galerie |

|

| Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, Crucifixion From a Missal (opening of the Canon, the Te Igitur) Italian (Perugia), c. 1472-1499 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 472, fol.131v |

|

| Raphael, The Citta di Castello Altar Italian, 1502-1503 London, National Gallery |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Crucifixion from the Large Passion German, 1510 Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum |

|

| Dominicus Custos, Crucifixion Flemish, c. 1580-1612 Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek |

By the 15th century more allegorical images appeared, alongside the traditional Crucifixion image. In these images Christ Himself now purposefully directs a stream of His Blood, usually from the wound in His side, into a vessel held by an angel or by the personification of Faith.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, The Blood of the Redeemer Italian, c. 1460-1465 London, National Gallery |

|

| Christ and Charity German, c. 1470 Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Museum & Foundation Corboud |

|

| Francesco Granacci, Christ the Redeemer Italian, Early 16th Century (1500-1543) Cardiff (UK), National Museum of Wales |

|

| Beham (Hans) Sebald, The Man of Sorrows at the Foot of the Cross German, 1520 Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum |

|

| Christ with Instruments of the Passion From the Hours of Charles V Flemish (Brussels), c. 1535-1545 New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M 696, fol. 37v |

By the end of the 15th century some images dispensed with specific references to the event of the Crucifixion and placed Christ’s self-given Blood into a more timeless realm, a reminder that the effects of the Crucifixion did not stop with the event, but continue to have impact in the present.

|

| Jesu Salvator Mundi Hand Colored Woodcut Dutch, Late 15th Century London, British Museum |

|

| The Savior Adored by Saint Catherine of Alexandria and a Female Donor From a Book of Hours Flemish (Tournai), 1535 The Hague, Koninklijk Bibliotheek MS KB 74 G 9, fol. 93v |

|

| Johann Sadeler after Maarten de Vos, The Church as Bride Receiving the Holy Spirit and Precious Blood Flemish, c. 1576-1590 Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek |

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, The Blood of Christ Venerated by Saints Ignatius of Loyola and Stanislaus Kostka Flemish, c. 1600-1619 London, British Museum |

|

| Hieronymous Wierix, The Blood of the Redeemer Flemish, c. 1600-1619 London, British Museum |

|

| Jacob Neefs after David Herregouts, Victory of the Kingdom of Christ Flemish, 1649 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum |

Some decades before Bernini created his image, Anthony van Dyck created one which is close to it in some aspects. Christ hangs, crucified, in a timeless location, while angels collect His blood in golden chalices. The image was widespread through Europe thanks to the engraving made after it by Wenceslaus Hollar.

|

| Anthony van Dyck, Crucifixion with Angels Flemish, c. 1632-1641 Toulouse, Musée des Augustins |

|

| Wenceslaus Hollar, after Anthony Van Dyck Crucifixion with Angels Czech, 1652 Amserdam, Rijksmuseum |

It is into this strain of images that Bernini’s image fits. The Cross is raised on high and the Blood of Christ pours into the sea below, a sea of endless mercy for sinners.

|

| After Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Sanguis Christi Italian, c. 1670 Ariccia, Museo del Barroco Romano One of three known versions of paintings after Bernini's drawing. |

©M.

Duffy, 2017

* The title comes from the first verse of the hymn Pange lingua, written

by St. Thomas Aquinas in 1264 for the Feast of Corpus Christi at the request of

Pope Urban IV.

___________________________________________________________

- The Anima Christi prayer dates from the early fourteenth century and was not, as was popularly believed, composed by St. Ignatius Loyola, although he did much to spread its use. See: Frisbee, Samuel. "Anima Christi" The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 1. New York, Robert Appleton Company, 1907. <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01515a.htm>.

- Lavin, Irving. “Bernini’s Death”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 54, No. 2 (June, 1972), pp. 158-186. See also, Lavin, Irving. “Bernini’s Sangue di Cristo Rediscovered”, Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, NJ, unpublished paper available at: <https://publications.ias.edu/sites/default/files/Lavin_Bernini%27sSangueDiCristoRediscovered-2015_Engl.pdf> Also: Petrucci, Francesco. “Il Sanguis Christi di Bernini”, Palazzo Chigi, Ariccia, Lazio, Italy. Available at < http://www.palazzochigiariccia.it/img/dipinti_inediti_barocco_romano/pdf/Bernini_Sanguis_Christi.pdf>

2 comments:

Love these. Thank you!

Excellent. There are other like the 1616 by Johan Wierix,and there are those of Christ standing on the alter before the priest.

Post a Comment